Details

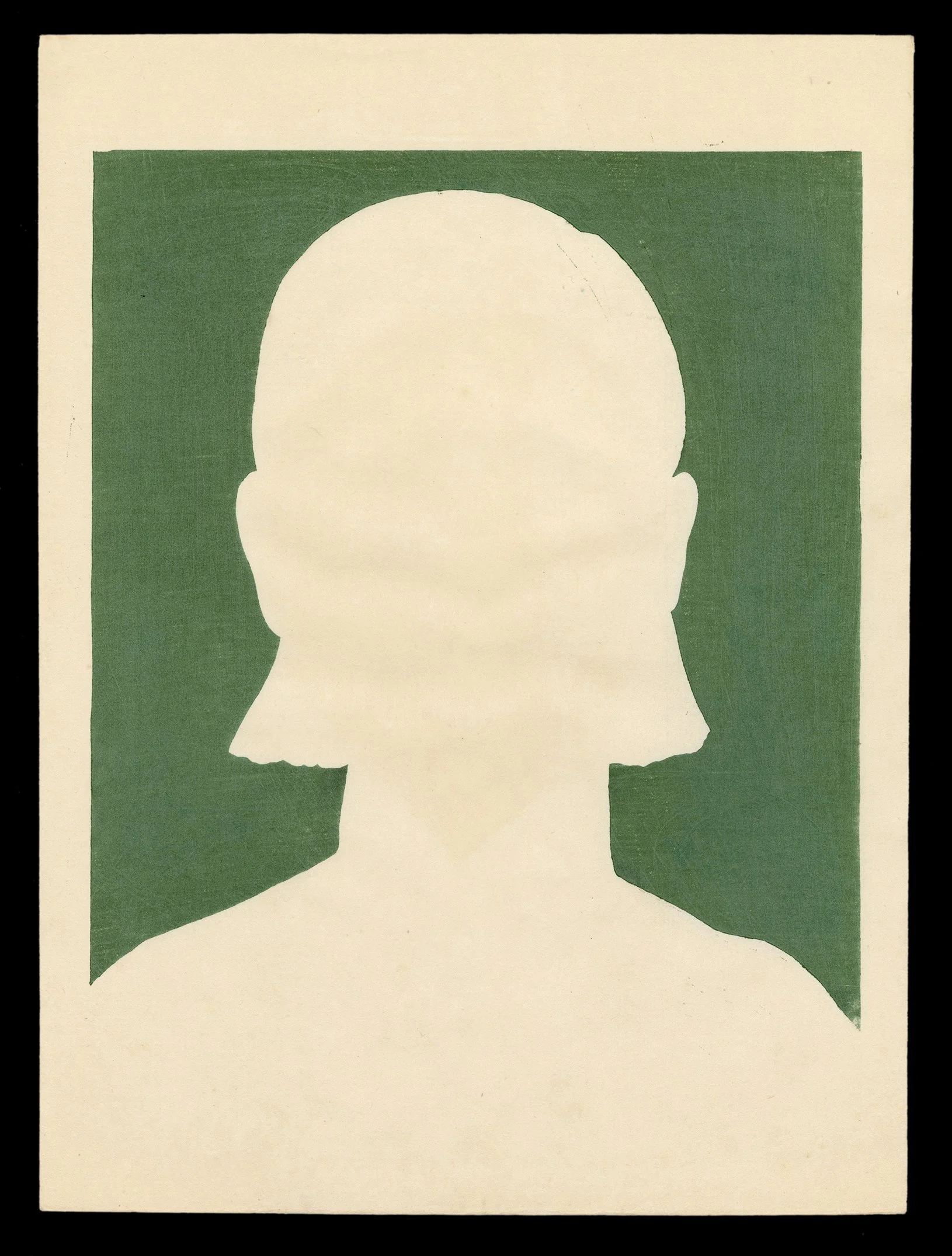

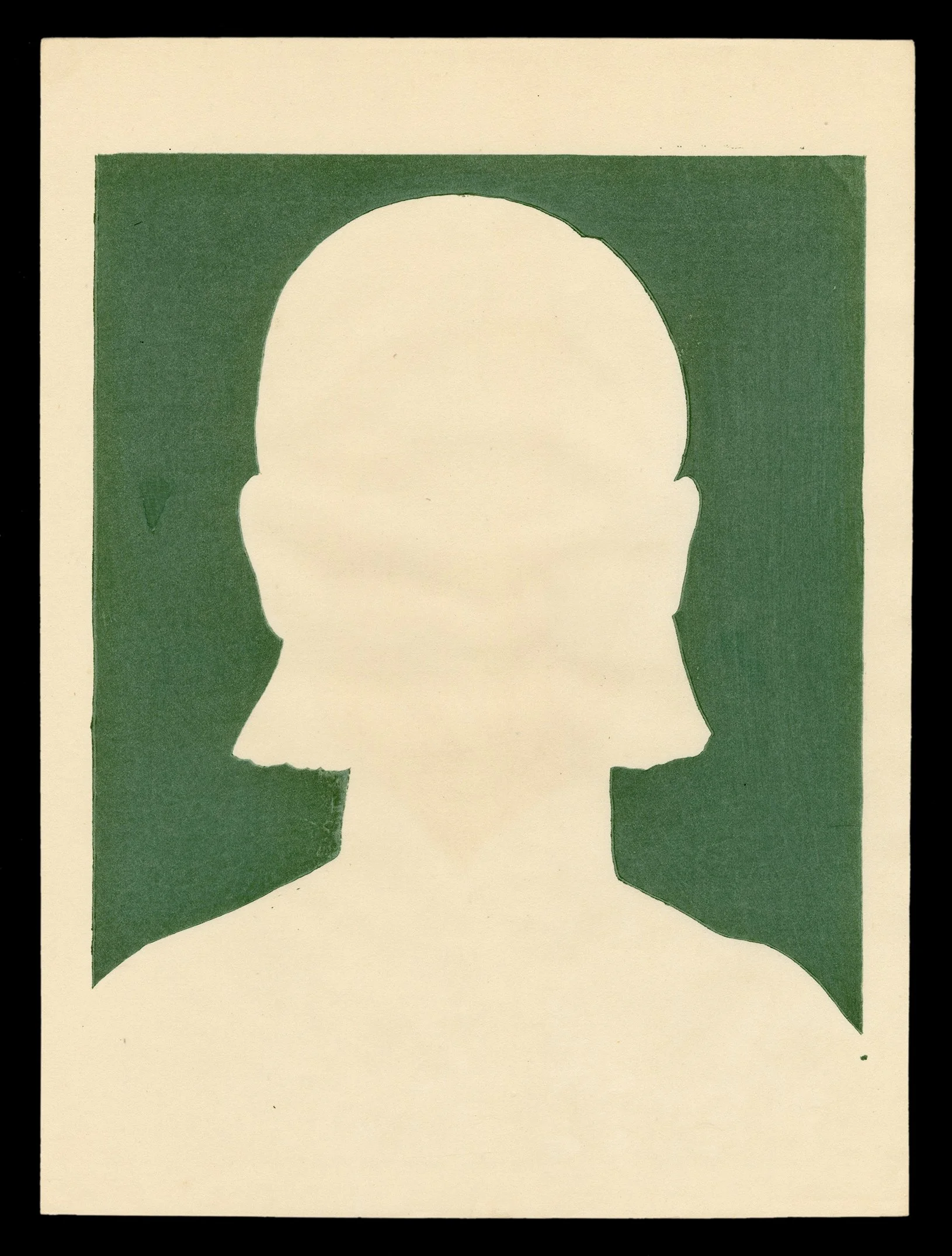

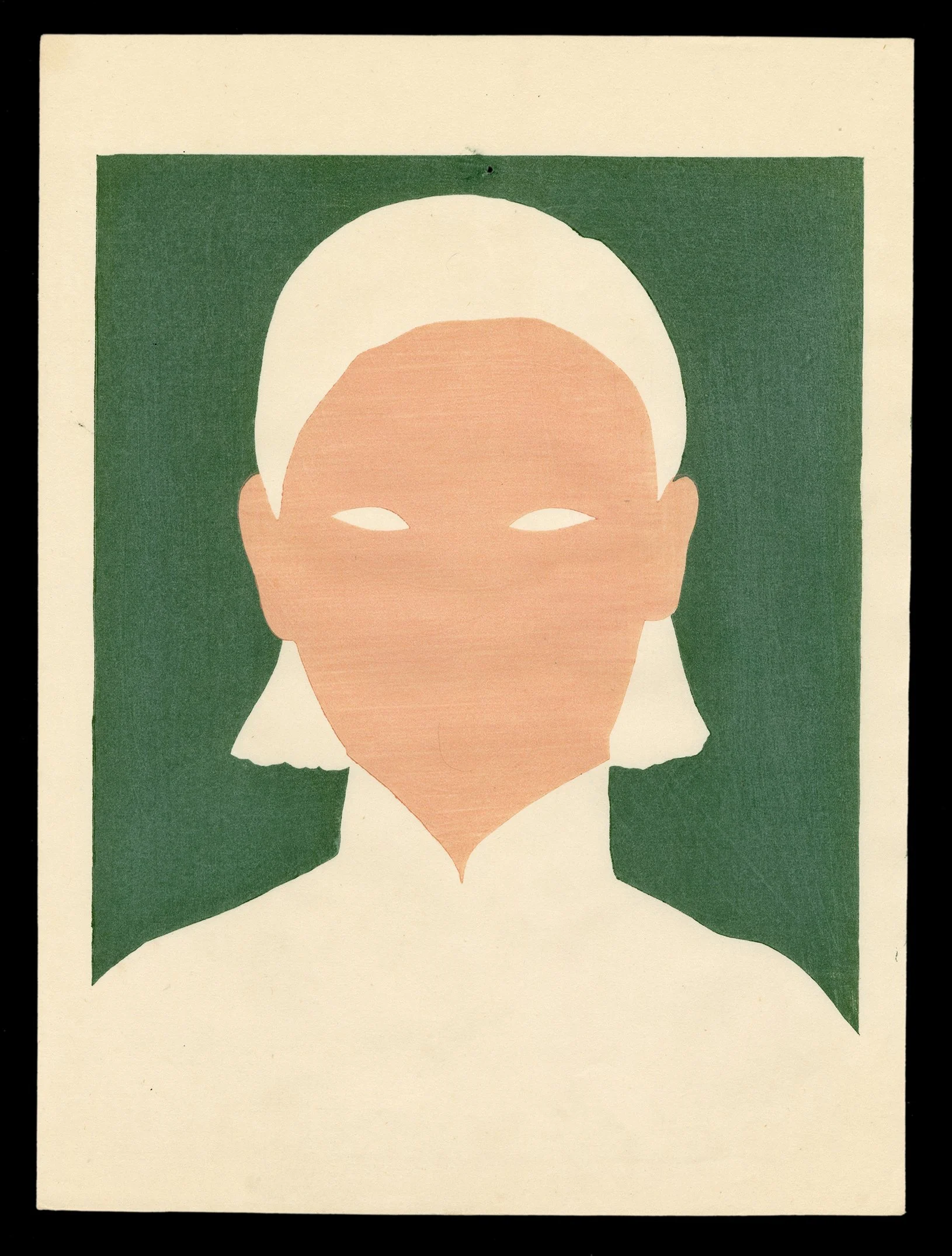

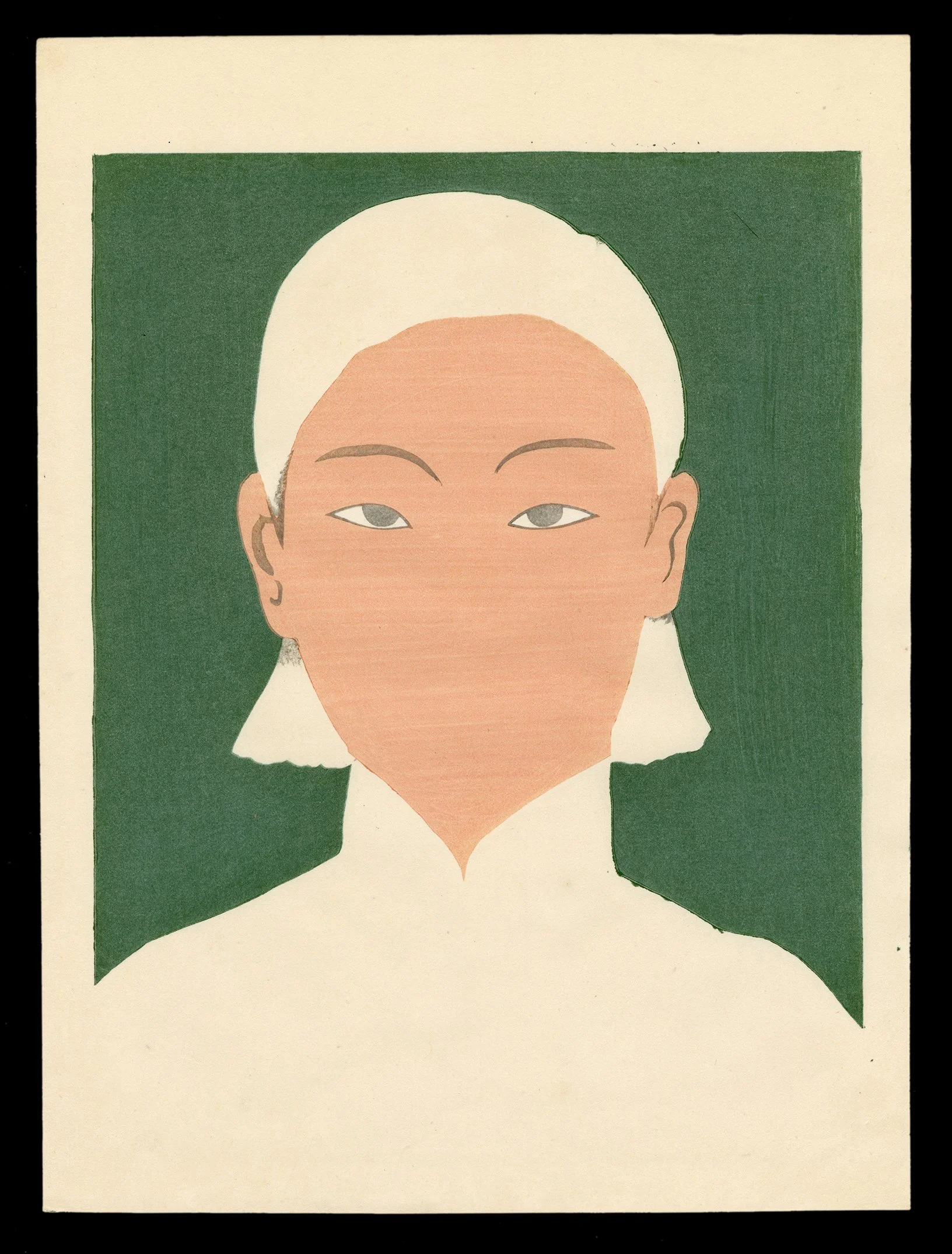

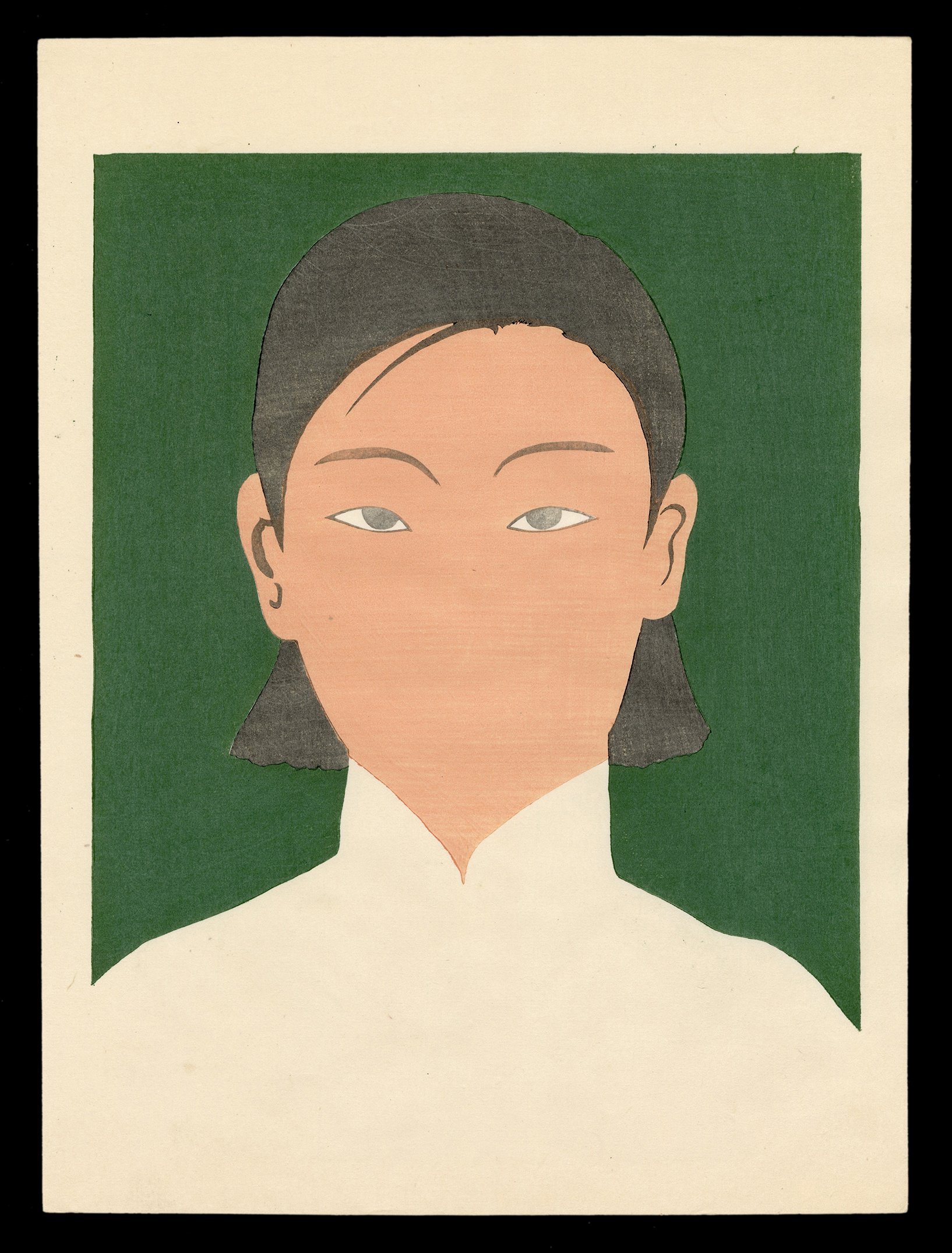

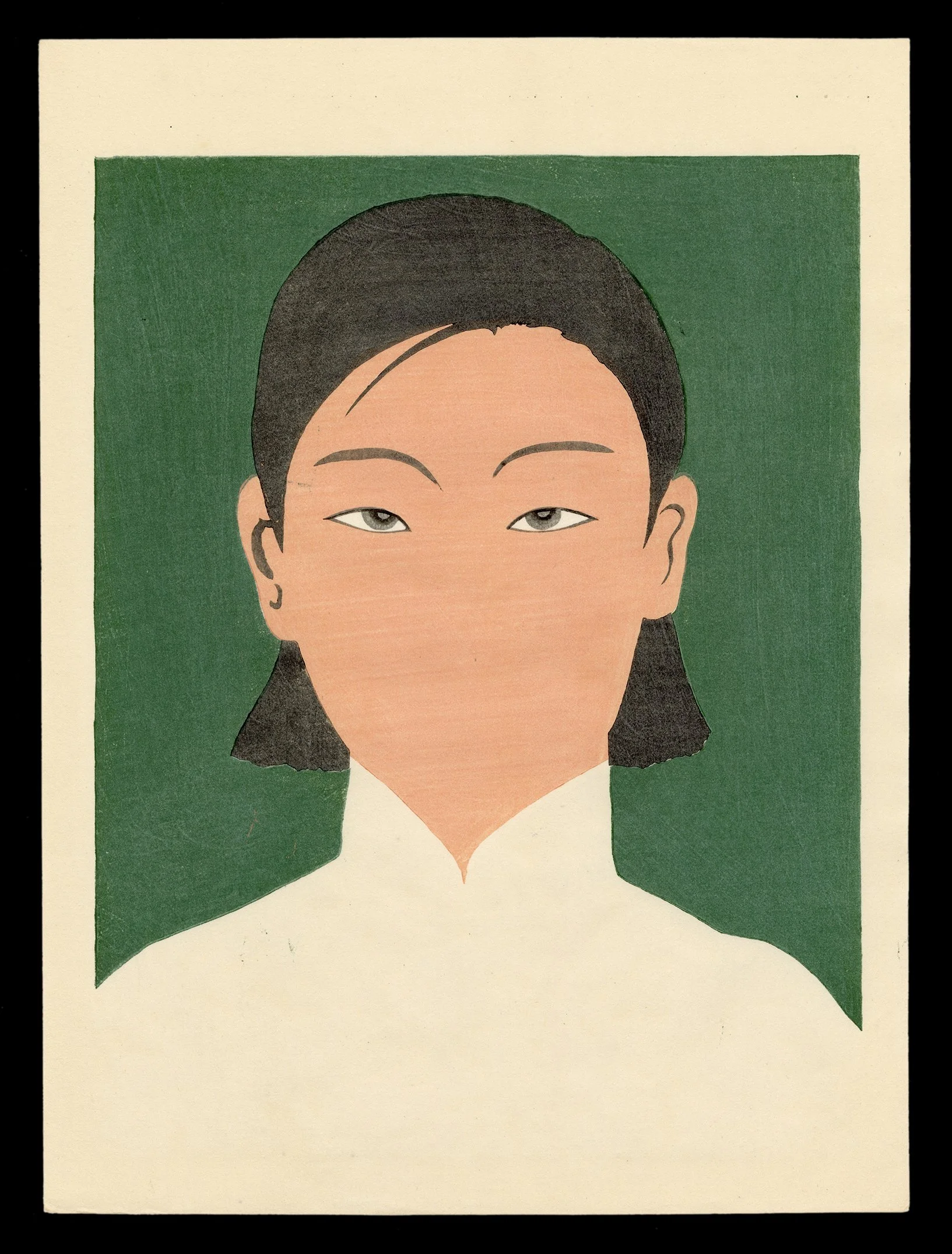

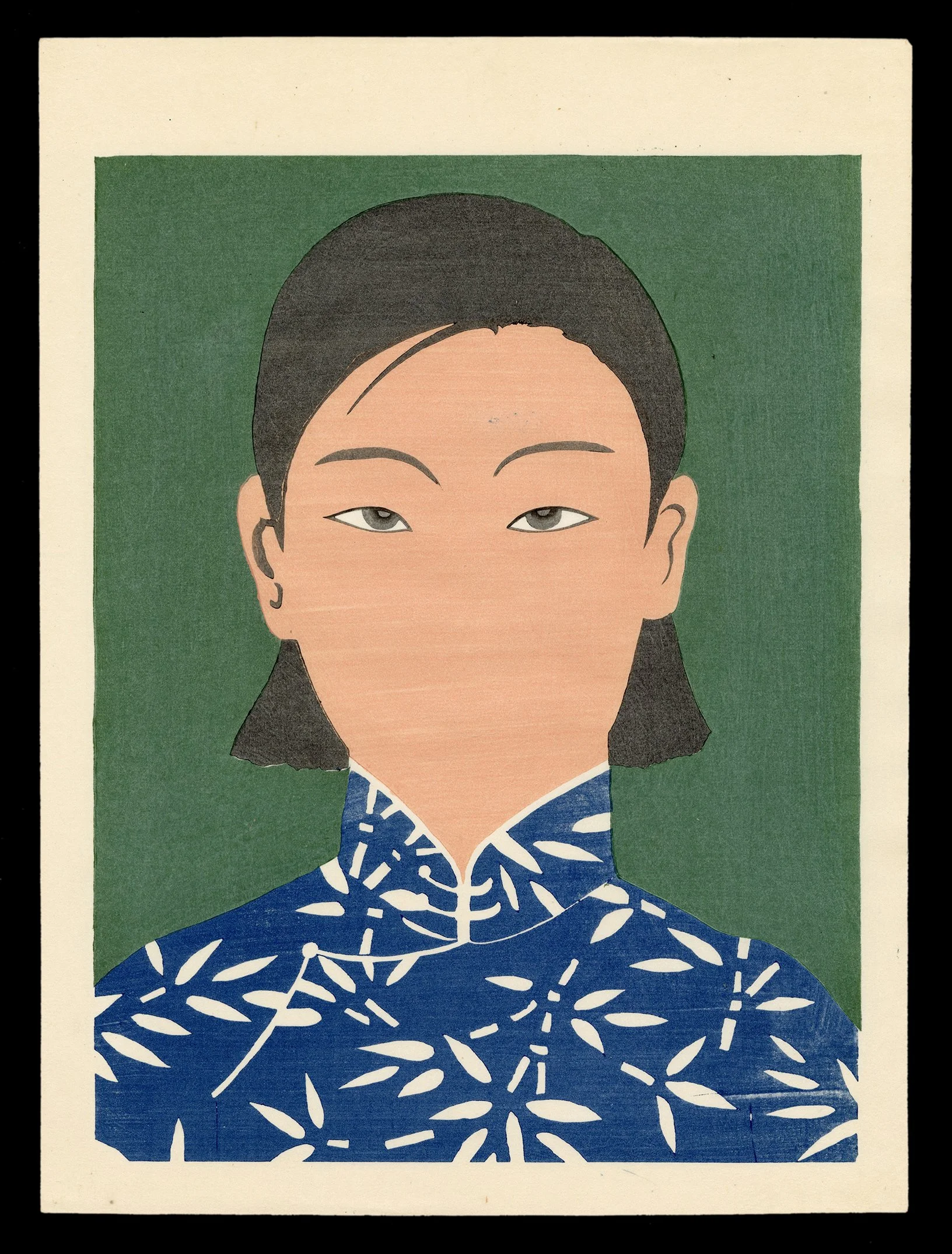

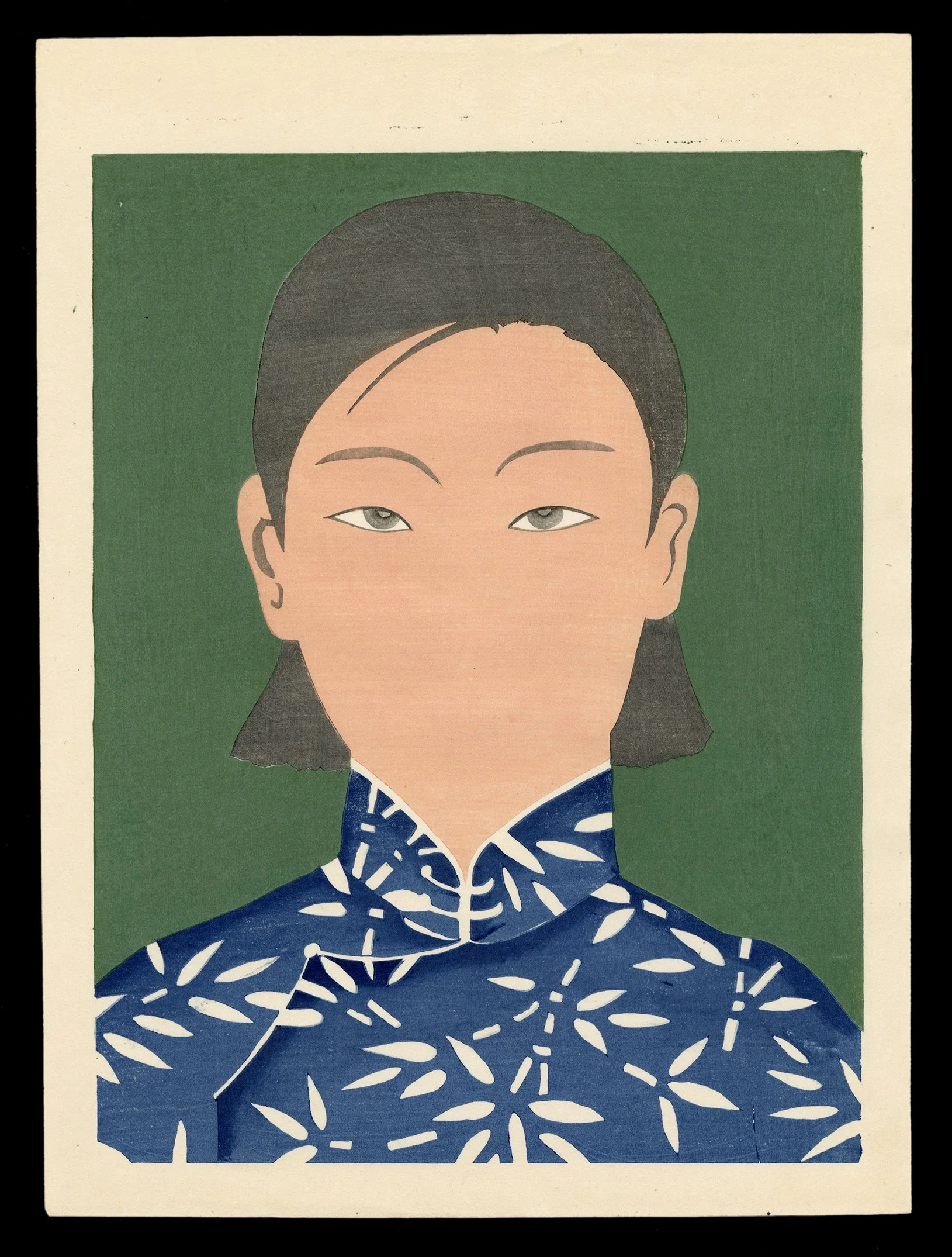

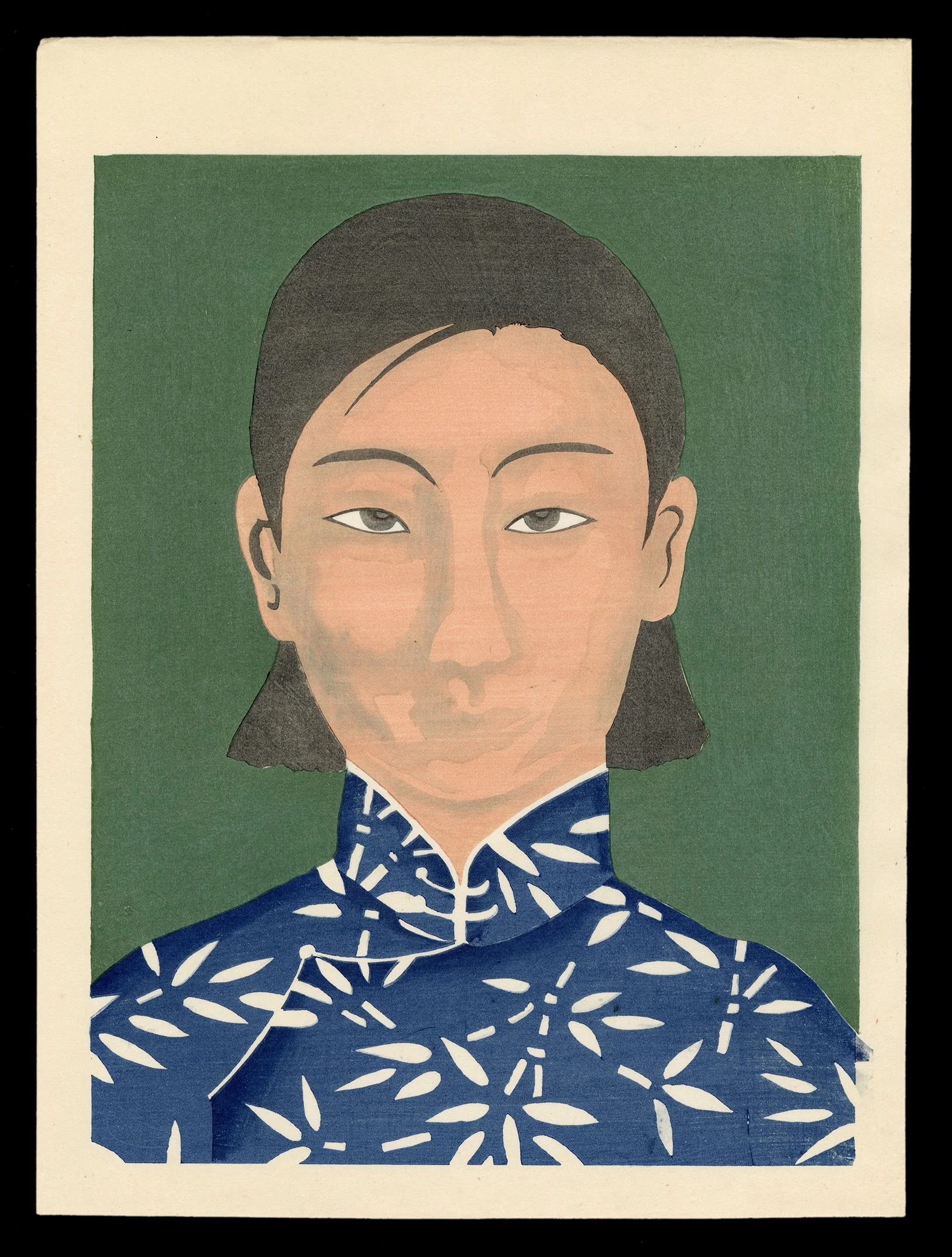

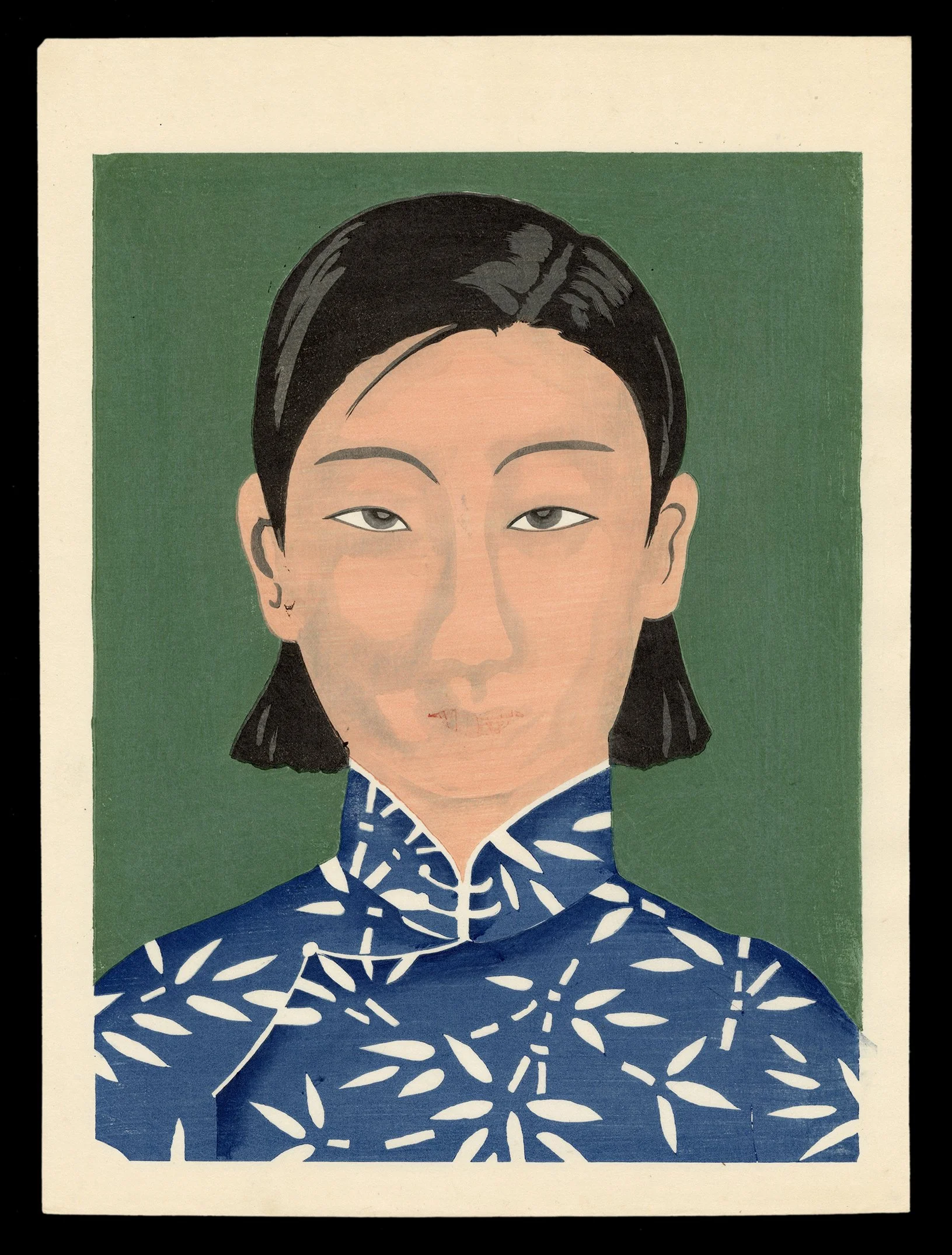

This arresting suite of progressive impressions titled Peking Girl by Masahide Asahi offers a rare and instructive window into the meticulous craft of Japanese woodblock printing in the early 20th century. Produced in the 1930—an era marked by renewed experimentation and technical precision in the Shin Hanga and Sosaku Hanga movements—this set reveals the complete development of a single print, from the initial silhouette block to the richly nuanced, full-color portrait. Each stage corresponds to a distinct carved block or layer of color, printed in succession with exacting registration.

The image itself depicts a young woman in a high-collared qipao dress patterned with bamboo leaves—stylized yet sensitive, with features rendered in soft tonal planes. The artist’s methodical progression begins with the flat background color, followed by the silhouette, skin tone, eyes, hair, and finally the intricate garment. As the suite unfolds, one perceives not only the technical layering but also the conceptual emergence of presence and identity from absence—an echo, perhaps, of the Buddhist notion of sokuhi: the form that is not-form, the self that emerges only in relation to the act of seeing.

Connoisseur's Note

Asahi, later known as Asahi Yasuhiro, was a central figure in the early 20th-century Sosaku-Hanga movement. Born in Kyoto, he emerged in the 1920s as a vigorous supporter of the Nihon Sosaku-Hanga Kyokai and later co-founded the Nihon Hanga Kyokai. His creative fingerprints can be found across many leading hanga magazines of the interwar period, and his participation in the seminal One Hundred Views of New Japan series further solidified his position within the vanguard of modern printmaking. Asahi’s internationalism—underscored by his travels to Europe and the U.S. in the 1930s—lent his work a cosmopolitan clarity while retaining the spare elegance of Kyoto’s aesthetic lineage.

In Peking Girl, these qualities converge. The print reflects both the disciplined layering of the printmaking process and a modern sensibility informed by travel, portraiture, and cross-cultural engagement. The subject’s stylized qipao and poised demeanor hint at a subtle dialogue between Japanese and Chinese aesthetics. The setting—a green ground devoid of narrative context—heightens the intensity of direct visual engagement, as if the girl is neither of a place nor of a time, but simply of the viewer’s moment.

What makes this suite particularly compelling is its educational and aesthetic value. Process sets of this completeness and clarity are exceedingly rare, usually retained by printers or studios for archival or demonstrative purposes. Each sheet not only maps the technical process but evokes the philosophy of woodblock art itself: a medium where form is built patiently from void, and where each layer is both discrete and inseparable. Asahi’s Peking Girl thus exists not only as a finished image but as a meditation on becoming—on art as the sum of invisible moments made visible through discipline, vision, and grace.